Tori is a fellow in the 2018 Leaders in Environment and Finance (LEAF) program. As part of this fellowship, Tori spent summer 2018 at Triangle J Council of Governments, where she helped investigate the administrative and financial aspects of alternative nutrient pollution management models and the legal barriers to implementation faced.

Despite disagreement over how nutrient pollution should be managed in the Jordan Lake watershed, stakeholders tend to agree on one thing: the Jordan Lake Nutrient Management Strategy, commonly known as the Jordan Lake Rules, have room for improvement. Many institutions in the public, private, and nonprofit sectors are working to figure out how to mitigate further degradation of water quality in Jordan Lake, in part by looking into alternative financial and governance options for a better regulatory framework. One of these institutions, Triangle J Council of Governments, has examined the framework of a regional watershed authority.

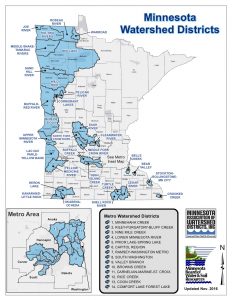

Across the United States, various jurisdictions are establishing regional watershed authorities that have the ability to address nutrient pollution. Two such models are found in Minnesota and Iowa. Each allows local political jurisdictions to come together and work with the state to run a regional watershed authority, and each provides some guidance that could be applicable for the current movement among local governments in the Jordan Lake watershed to establish a more collaborative nutrient management framework.

Minnesota Model

In 1990, Minnesota created state legislation allowing the establishment of regional watershed districts, the state’s term for regional watershed authorities. Under this legislation, a majority of political jurisdictions—either by population or number of political subdivisions—or a minimum number of citizens within the potential watershed district’s jurisdiction, must petition the state to form a watershed district. Once accepted by the state Board of Water and Soil Resources, the watershed district encompasses all jurisdictions within the geographic boundaries. Local governments within the district’s boundaries that did not originally wish to join are mandated to comply with its regulations.

Funding for the watershed district’s nutrient management projects is provided through assessments against abutting properties and taxes levied by the counties encompassed in the district. Tax burden per county is limited to the respective county’s net tax capacity relative to the net tax capacity of the watershed district. This revenue is generated in the form of ad valorem taxes with limitations on percentage of value and designated purposes, including organizational expenses, bond payoff, construction and implementation of water quality projects, repair and maintenance of aforementioned projects, and surveys and data acquisition.

Iowa Model

Iowa created legislation allowing for the formation and appropriation of funds to regional watershed authorities, called water management authorities (WMAs), in 2010. Iowan water management authorities are formed when two or more political subdivisions within the same watershed enter into an agreement with a basic administrative framework that has been standardized by the state. Contrary to the Minnesotan model, membership in the water management authority is voluntary, but all political subdivisions within the watershed must be notified of its formation and invited to join within thirty days of establishment.

WMAs initially rely on state funding, but then turn to alternative funding sources once they have been established and have created watershed plans. Project funds have diverse funding sources, including state-appropriated funds, money collected by the state Department of Natural Resources, private and public donations, and interest on money within the fund, primarily because there is little state money dedicated to these projects. Individual jurisdictions within WMAs may also raise their own revenue.

Why are these models good examples for North Carolina and Jordan Lake?

These programs address some of the equity, efficiency, and cooperation concerns present in the Jordan Lake Rules. In these models, costs of nutrient management projects are spread among all jurisdictions in a watershed or even a whole state, in contrast to the Jordan Rules’ “polluter pays” approach, where cost burdens are concentrated in upstream communities while beneficiaries downstream contribute little to no funding toward nutrient management. By pooling together funds, the watershed authorities can more easily target the most cost-effective projects.

These funding arrangements also match up well with their respective administration models. Under the voluntary watershed authority model, membership is not required, but political subdivisions face little to no extra cost in joining so there are few financial barriers to garnering widespread governmental involvement in a watershed authority. On the flip side, the mandatory watershed authority model which requires member governments to directly contribute funding largely eliminates the free rider problem by mandating membership.

The Jordan Rules, in their current state of delay, combine two incompatible aspects of the two models described above – voluntary adherence to the Rules and direct costs imposed on member jurisdictions for this compliance. Additionally, there is currently no pooling mechanism for nutrient management funds for Jordan Lake, delays or not. The end result of this combination is nutrient management that does not meet the region’s potential.

Potential Challenges

Despite the benefits of the Iowan and Minnesotan models, creating a regional watershed authority is not a silver bullet and would not be a simple process. To even form a watershed authority in the first place, political subdivisions with diverse interests and existing local ordinances would need to come to a general agreement on the watershed authority’s administrative framework, which they would then need to present to the North Carolina General Assembly as an alternative to the Jordan Rules. If the legislature accepted their proposal, then evaluations of project costs and benefits and local restrictions on project implementation would need to be run, which would take time. Additionally, there may never be enough revenue-raising potential to completely clean up the lake.

Although water quality in Jordan Lake may be a work in progress, there are models around the country that can help inform better processes to generate revenue, pool funds, and spend money to more effectively improve nutrient management in the Jordan Lake region and throughout the state. To see the Environmental Finance Center’s current work in the UNC Nutrient Management Study, click here.

Tori Molyneaux is a LEAF Fellow double majoring in Economics and Political Science, minoring in Environmental Science and Studies at UNC-Chapel Hill. Prior to working with the EFC, Tori interned as a research analyst for White Oak Partners and as the Clean Water and Beyond Gas Intern at the Maryland Chapter of the Sierra Club.