Post by Omid Barr, Evan Liebgott, and Stephen Lapp at the UNC EFC

Last year, UNC Chapel Hill received a $1 million donation from Champion Athleticwear to establish the Champion Sustainability Fund at Carolina.[1] This donation includes a Green Revolving Fund (GRF) program, a growing trend among universities.

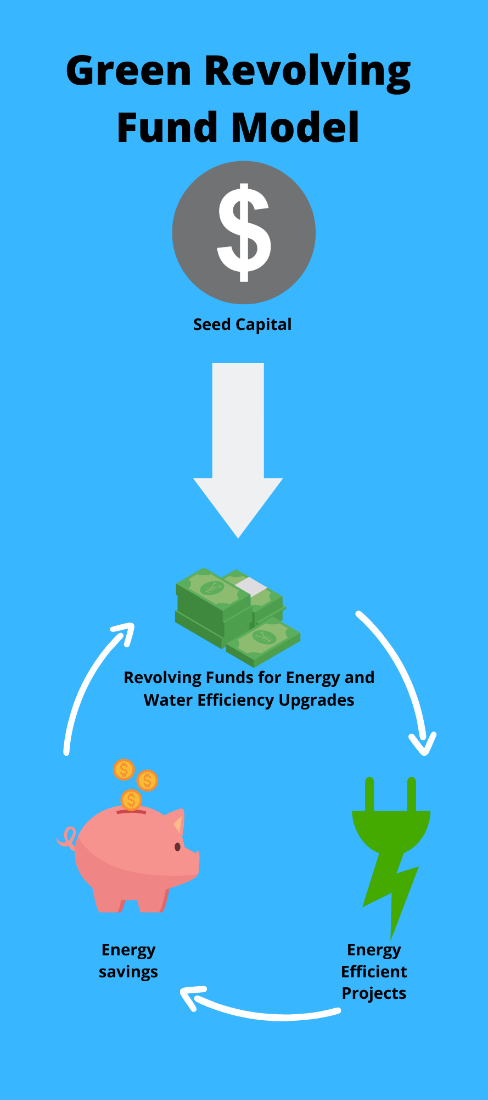

A revolving fund is a financing mechanism in which some or all the debt payments are recycled for future project funding. Readers in the water and wastewater utility sector may recognize the term and think of examples such as the Clean Water State Revolving Fund (CWSRF) and the Drinking Water State Revolving Fund (DWSRF). These Funds are federal-state partnerships that provide communities with a source of low-cost financing for water and wastewater projects. The revolving fund model has been adapted by universities to create GRFs, internal investment structures that provide financing to parties within the university to improve campus sustainability.

A major roadblock in campus “greening” is the high initial cost of financing sustainability measures. GRFs mitigate this problem by providing upfront financing to invest in energy efficiency upgrades and other projects that decrease resource use, thereby lowering operating expenses. These operational savings are returned to the fund and reinvested in future projects, allowing the fund to grow indefinitely.

How does a GRF get started?

A variety of sources can provide the upfront financing, or seed capital, for a GRF:

- Private donations

- State university system

- Utility Rebates

- External grants

- Bond financing

- Funds from within the university

How are disbursed loans repaid?

The project applicant (e.g., department, school, campus group, etc.) repays their loans through savings derived from the implementation of the project, but there is no one-size fits all model for structuring a GRF accounting mechanism. If the funds are disbursed via a loan, repayment can be determined with upfront estimates of savings. If funds are transferred to the applicant or a central facilities department, repayment can be made via a transfer of funds back into the GRF from a centrally managed operating budget. Oftentimes funds incorporate elements of both these models.

Who has the authority to govern GRFs?

Typically, a GRF is governed by a board or committee whose specific purpose is to administer the fund. These bodies may be composed of a mixture of faculty, staff, students, and occasionally non-affiliated community members.

A Successful GRF: Portland State University

While the goal of any GRF is to enhance sustainability efforts and provide cost savings to finance future projects, the details, such as structure, size, management, project criteria, funding sources, and payback requirements, can vary greatly.

Looking at the case of Portland State (PSU), the University received $500,000 in seed capital from the State of Oregon in 2013 to create a GRF. The GRF is administered by the University’s Campus Sustainability Office in collaboration with Facilities & Property Management, Capital Projects & Construction, the Engineering faculty, and the Planning, Construction, and Real Estate team.

PSU employs both a set of required and preferred project criteria. Repayment of loans is dependent on the number and type of criteria incorporated into a project. If only the required criteria are met, projects must repay the loan within ten years. If at least 2 of the preferred criteria are met, then GRF loanees have 15 years to pay back the loan.

The required project criteria include:

- Providing a tangible return on investment, measured by savings in the utilities budget.

- The project must improve the condition of a building resulting in a conservation of resources.

- A sustainability benefit demonstrating a reduction in PSU’s environmental and economic impact while promoting equity.

The preferred criteria encourage projects that improve sustainability on multiple fronts and maximize the environmental impact of dollars invested. These criteria include:

- Encouraging education among the campus community to learn about energy conservation.

- Informing future sustainability efforts.

- Promoting PSU’s institutional vision to be a leader in campus sustainability.

- Incorporating mechanisms for verifying energy savings.

- Selecting projects that complement existing work.

- Addressing racial equity.

Including racial equity into the project selection process is an uncommon feature for a GRF. The Planning and Sustainability Office at PSU incorporated a school-wide commitment to racial justice into their GRF model by developing a prioritization tool to evaluate proposed building improvements using data from an equity analysis. This five-year analysis comparing student and employee demographics against building energy use intensity (EUI) and building quality (looking at items such as access to daylight and LED upgrades). Some campus buildings with high EUIs and/or lesser building quality served a higher percentage of students and staff of color. The University hopes to use this new tool to prioritize future capital investments, including GRF projects.

Thus far, PSU has funded more than 25 projects using its GRF. At its conception, the project selection process was conducted entirely by the GRF’s committee members. Later, this process was altered so that departments could submit project ideas, allowing departments with less funding to make improvements and purchase new appliances. For more information, visit https://www.pdx.edu/sustainability/green-revolving-fund.

The University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill GRF

Using the GRF model, the Champion Sustainability Fund at Carolina (CSF) will encourage projects that focus on sustainability education and energy efficiency. This initiative is part of the broader Sustainable Carolina program, which aims to continue reductions in the university’s environmental impact.[2] The eligibility criteria for applications are currently in development, but projects must involve water or energy savings. Additional review criteria may include payback period, cost, total savings, duration of implementation, innovation, and educational opportunities.

To be effective, sustainability must not only be economically viable and environmentally sound, but socially just as well. Too often in the field of sustainability, equity is ignored to focus on more easily measurable environmental metrics, like gallons of water saved or emissions reduced. Following PSU’s lead, the UNC-CH may be able to elevate its sustainability status and address social equity by incorporating a similar equity assessment of building performance and demographics into its project criteria.

[1] https://www.unc.edu/posts/2021/04/22/innovative-sustainability-programs-champion-sustainability-fund/

[2] https://www.unc.edu/posts/2021/04/16/climate-action-plan/