As of 2014, NOAA estimated that about 40 percent of the US population lives in a county on the coast and these coastal counties are responsible for 56 million jobs. As a nation, we have developed heavily along the coastlines, building large and valuable assets on property that may erode. As communities along the southeastern coastline have experienced and can likely attest to, there are very few viable options for slowing coastal erosion that do not either cause more erosion downdrift or damage to coastal ecosystems. To date, most communities have found beach nourishment to be the most viable option. So what is beach nourishment and how do we pay for it? Read on for answers to these questions and more:

What is beach nourishment?

Nourishment goes by many names, including, but not limited to “beach nourishment,” “beach renourishment,” “beach replenishment,” and “coastline stabilization,” but they all generally mean the same thing: dredging sand from the nearshore environment (<1 kilometer offshore, inlets, harbors, etc.), and pumping it to the coastline. From there, heavy machinery (e.g. bulldozer) moves the sand around to create a wide, smooth beach. The wider beach helps protect communities from storms and erosion, and provides additional area for recreation (Video: More Beach to Love, Dare County, North Carolina).

And that’s it. Sounds easy and inexpensive, right? HINT: it is not that easy, nor is it inexpensive.

Before (left) and After (right) a Nourishment Project: Ocean City, Maryland

Why beach nourishment?

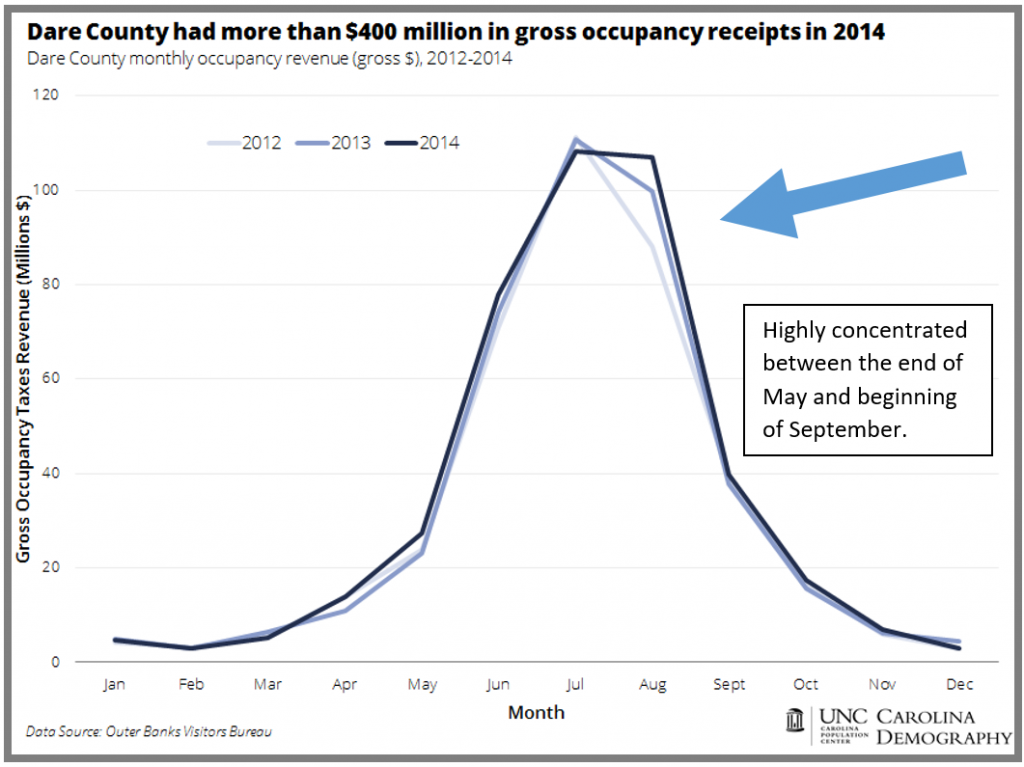

Beaches in the United States, specifically throughout the Southeast, have become the centerpiece of a large and prosperous tourism industry. For some areas, including communities along North Carolina and South Carolina coastlines, this industry is highly concentrated during the summer months, generating large revenues for municipalities and business owners but leaving winter months quiet. Individuals and families from across the globe flock to sandy beaches, seeking long sunny days, warm ocean temperatures, and plenty of beach for relaxing or recreating. Due to coastal erosion, sometimes this beach can start to erode over time. Sandy beaches are highly dynamic, eroding in some spots and accreting in others, but rarely following the straight lines engineered during the Works Progress Administration era.

Concentration of Occupancy Receipts in Dare County, 2014

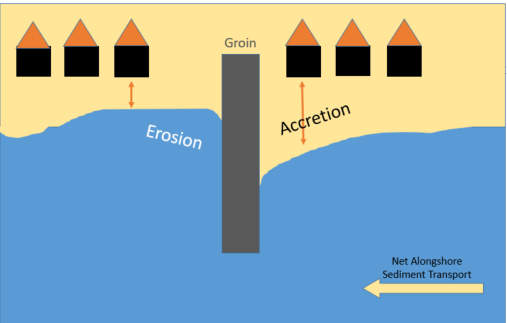

As coastlines shift the beach can begin to shrink, limiting the space available for recreation and eventually putting oceanfront properties at risk. To combat this issue, the federal government began appropriating funds to the Army Corps of Engineers to experiment with different methods of preventing erosion. Hard structures, like groins and breakwaters, cause accretion of sand on one side, thus building the beach. But because they block the natural flow of sand, can cause serious erosion downdrift.

Illustration of Erosion and Accretion Due to Hard Structures along Coastlines

For this reason, the Army Corps of Engineers now primarily relies on beach nourishment projects to restore beach width. Because the sand is dredged from offshore, the loss of sand is outside of the beach and thus not subjecting downdrift communities to additional erosion. In addition, engineers and scientists have gotten very skilled in matching sand grain sizes, thus reducing the environmental impact.

How much does it cost?

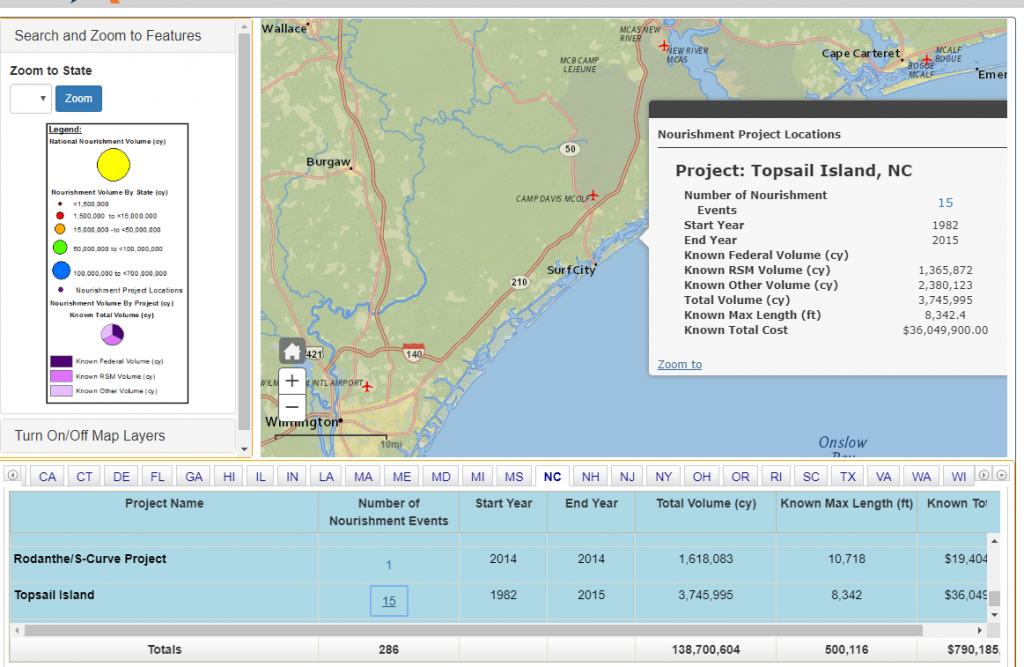

Nourishment is very capital intensive and has large fixed costs. It involves a lot of time, equipment, and careful planning to ensure that the project meets the needs of the community, but does not fall during the busy season and harm the local economy. Just getting equipment to the beach can run up a large bill, so there is some incentive to nourishing a large area all at once and introducing some periodicity to nourishment. The costs can vary widely depending on the community’s needs and availability of viable sand, but all are on the order of millions of dollars. The American Shore and Beach Preservation Association (ASBPA) has a web resource that provides historical data on project length, volume, and cost.

For example, in 2015 Topsail Island, North Carolina, completed its twenty-first nourishment project. It spread 835,123 cubic yards of sand and cost $10.3 Million.

The ASBPA National Beach Nourishment Database

Who pays for it?

Historically, federal subsidy aided local governments threatened by coastal erosion. For communities grandfathered in to federal assistance, a cost-sharing formula is used. Prior to 2000, the federal government provided roughly two-thirds of project costs, with the assurance the community receiving assistance could foot the other one third. For periodic nourishment, this cost-sharing has since been amended to 50:50. This remaining one third to one half of costs is often shared between the local government units and the state, but how the cost sharing works tends to vary on a state-by-state basis.

This is beginning to change. Federal appropriations for beach nourishment are stagnant and often on the table for additional cuts, and this stagnant budget is met with increasing need. More communities are being built along coastlines, driving economic development and, consequently, public interest in wide beaches. As a result, the burden of paying for nourishment projects is shifting. As federal subsidies shrink, local governments are employing creativity to close the gap. For Dare County, for example, this includes using a county Beach Nourishment Fund that collects occupancy tax revenues to cover a share of the project cost and local government debt financing for the remaining amount.

Some of these coastal communities, however, are small. Like in the Outer Banks, or along other barrier island communities, the municipalities often have few methods of revenue generation in addition to a very small contingency of properties to tax to pay debt service payments. To make matters more challenging, small towns often struggle to compete for federal funds. The federal government often chooses projects based on the ratio of project costs (i.e. the cost to nourish) to project benefits (i.e. the economic impact and value of infrastructure protected). For larger coastal municipalities, there is more infrastructure to protect.

An Example of a “Thin” Community: Kill Devil Hills, NC

How do local governments generate this revenue?

In many cases, local governments are still receiving federal subsidy, so the required revenues must only equal approximately one third of the project costs. Often, these are paid for through “shoreline stabilization funds” or something similar, and there is typically some cost-sharing on the local and state level.

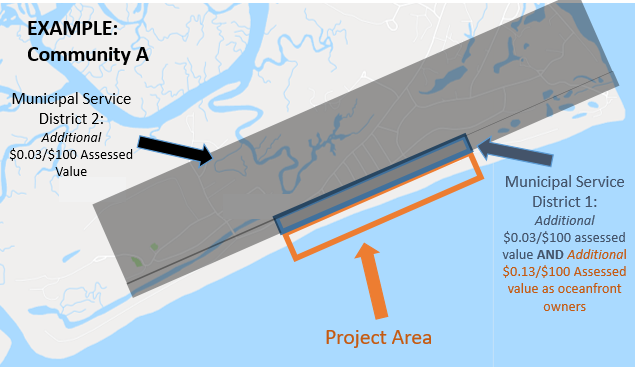

For communities that did not apply for federal assistance early on or do not have the infrastructure to drive a competitive cost-benefit analysis, the revenue generation looks a little different. In Dare County, for example, occupancy taxes go to a county fund. This leaves sales taxes and property taxes as methods of revenue generation. For Dare County, the recent trend has been establishing Municipal Service Districts that pay an additional millage rate reflecting their benefit from the project. In theory, the distribution of project benefits are not uniform throughout the community. Property owners on the oceanfront benefit the most, because the risk of property loss is greatly reduced with a wider beach. Everyone else in the community also benefits from the project, either economically from continued tourism, recreationally from a wider beach, or from storm surge protection, but less so than those on the oceanfront.

In an attempt to follow the benefit/cost principle, communities often create two or more Municipal Service Districts (MSDs): one or more that encompass a large group of properties within the municipality, and one encompassing the oceanfront properties within the project area. The former group(s) pay a much smaller millage rate than the latter, but all pay the additional fee every year for the life of the project.

An Example of Structuring MSDs to Recover Project Costs*

What are the challenges with funding beach nourishment projects?

Because communities are using debt service (and often general obligation bonds) to cover project costs they must have buy-in from the public. Even as some communities begin using special obligation bonds, which do not require voter approval, the threat of public discontent can lengthen the establishment of MSDs and project budgeting. Because erosion is so visible to community members, most are on board with project implementation. However, the challenging part is finding that ever-elusive sweet spot of millage rates that mirrors the project benefits, has public support, and covers the necessary costs.

In the future, climate change is expected to cause sea level rise that could shorten the useful life of these projects, requiring communities to raise revenues on a more frequent basis. No perfect equation currently exists for equating project costs to project benefits, especially when project benefits are hard to quantify, but with increasing need and a shift from federal to local responsibility, financing beach nourishment projects is likely to remain a topical issue for local governments of coastal communities into the future.

Austin Thompson joined the EFC at UNC in 2018 as a project director. In this role, she conducts applied research and provides technical assistance and training for environmental service providers. Thompson holds a BS in Biological Sciences from the University of South Carolina and a Master’s of Environmental Management from Duke University, with a concentration in Environmental Economics and Policy.

2 Responses to “Growing Economies and Shrinking Coastlines: Financing Wider Beaches”

Dawn Kitai

How interesting that you talk about what beach nourishment is and how it helps. I love the beach and like to go there when I have things to reflect on in my life like I do this month. I will find an excellent beach-view hotel so that I can take a trip.

ayhan han

Good nice post.