Depending on where you live, you might have wandered through scaffolding that supports new high-rises in a rapidly-developing city, or driven past brand new housing developments cropping up where wetlands used to thrive. You might have wondered about the environmental impacts of construction and the long-term impacts of newly paved surfaces replacing natural habitat. Fortunately, the EPA requires developers to consider these impacts prior to construction in order to avoid adverse impacts, minimize their impacts, and finally, provide compensatory mitigation for the unavoidable impacts to wetlands. But how do local and state governments organize systems and structures to manage these processes?

The United States has a goal to achieve no net loss of wetlands, despite growth and construction. The “mitigation sequence” is to “avoid,” “minimize” and finally “compensate,” when it comes to impacts to aquatic resources. First, a proposed project must take all appropriate measures to avoid and minimize adverse impacts, but when adverse impacts are unavoidable, compensatory mitigation measures are taken. The EPA has also established a hierarchy for wetland compensation. The first preference is to establish a mitigation bank, in which credits are available for purchase from a wetland that has been restored, established, or enhanced, for the purpose of providing compensation for unavoidable impacts. If conditions exist that prevent the mitigation bank option, then an In-Lieu Fee (IFL) can be considered, in which a program sponsor pools resources to maintain a mitigation site. Through funding from EPA’s Office of Wetlands, Oceans, and Watersheds, the EFC has been researching In-Lieu Fee (ILF) program operations to assist interested states and communities in creating and implementing these types of programs.

What is an In-Lieu Fee?

An ILF is one method of “compensatory mitigation” for damages to the environment. It is used to compensate for impacts or unavoidable losses to wetlands and streams due to development, road-construction, or other projects.

With ILFs, mitigation occurs when a permittee provides funds to an in-lieu-fee sponsor, e.g. a public agency or non-profit organization. In most cases, the sponsor collects funds from multiple permittees in order to pool the financial resources necessary to plan for, build, and maintain the mitigation site. Like mitigation banking, in-lieu fee mitigation is often”off-site.” Unlike mitigation banking, it typically occurs after the permitted impacts.

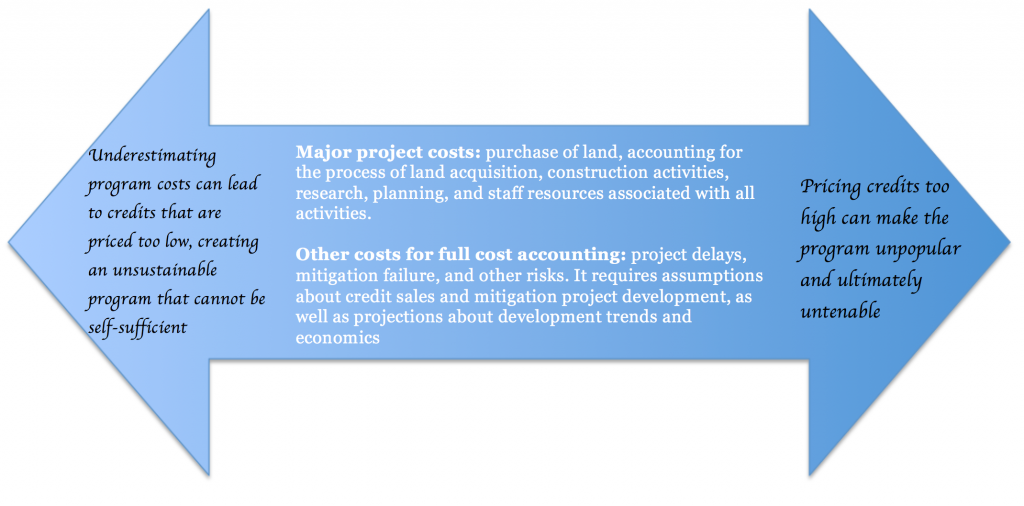

Developing an ILF program and Understanding How Credit-Pricing Decisions are Made

Under this project, EFC staff interviewed ten ILF program administrators, USACE officials, and representatives from state agencies involved in the Section 404 permitting or approval process. ILF programs require documentation and standardization for credit fees, but the elements that drive credit prices are often highly variable. So how do program sponsors overcome the challenge of analyzing, forecasting, and projecting?

Lessons Learned

From these interviews, the EFC learned that agencies creating ILF programs must solve a puzzle that fits into the EPA framework. The puzzle pieces include data and expert opinions, but some puzzle pieces might be missing, or have vague edges. A few other lessons we learned about this puzzle:

Detailed guidance doesn’t mean an ILF program can just use a “template” or borrow a framework to draft the Program Instrument.

- A 2008 rule provides specific, detailed instruction on what must be included in an ILF Program Instrument. However, a state or local government, or nonprofit agency, cannot simply “fill in the blanks,” since credit pricing and advance credit release require a deep understanding of the economic and environmental landscape. An in-depth analysis helps to collect all the pieces of information to ultimately complete the puzzle.

- Furthermore, administering an ILF program is complex and requires staff who have expertise in ecosystems and environmental services, as well as staff who specialize in financial accounting and budget management. Cooperation between different departments or collaboration of diverse skill sets is required to put the puzzle together.

- ILF programs in different states share a common purpose, but are modeled quite differently, depending on enabling policies, geographic and topographical considerations, and demand for wetland credits. Borrowed pieces from another state’s ILF program may not fit into your own puzzle.

It takes a village

- Successful ILF programs require active and engaged stakeholders to provide context-specific guidance, feedback, and oversight in the creation and implementation of the ILF program. Just like the concept of pooling the in-lieu fees to create a cohesive, environmentally beneficial mitigation project that is superior to multiple small, unlinked permittee-responsible mitigation projects, a successful ILF program should mesh with the resources, infrastructure, and supply and demand for credits. Stakeholders can bring additional puzzle pieces to the table.

A balancing act

A major lesson that all of the interviewees echoed was that it is important to incorporate flexibility into the ILF program from the beginning. Having an adaptive program, with the ability to adjust prices on a regular basis, is critical for withstanding inevitable changes to the economy and environment. Because, sometimes, when we finally have the puzzle put together, the picture changes!

This blog was co-authored by Michelle Madeley who worked at the EFC at UNC in the spring of 2015.

(Thank you to Rich Mogensen for pointing out a correction in the initial blog post concerning the mitigation hierarchy interpretation.)