Stormwater, or simply runoff, is precipitation that does not soak into the ground. Stormwater management involves controlling the quantity and quality of stormwater as it eventually enters waterways via ditches, culverts, and stormwater drains. Success stormwater management ensures public health and safety. Stormwater management programs may also be responsible for regulatory compliance, public education, and other requirements. It thus will come as no surprise that managing stormwater is expensive.

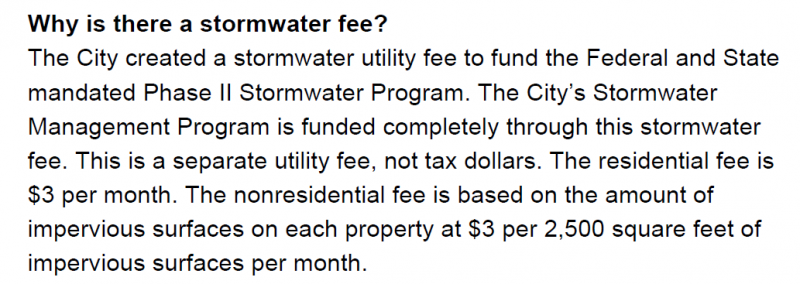

In North Carolina, stormwater is defined by statute as a public enterprise just like water, sewer, and solid waste. As a public enterprise, local governments can charge a stormwater utility fee to raise revenues to fund a stormwater management program. Statewide total revenues from stormwater fees have exceeded total revenues from solid waste fees. But are local governments generating stormwater revenues in an equitable way? What is meant by ‘equitable?’ Is one stormwater fee structure more equitable than the rest?

First, some definitions and examples of stormwater fee structures.

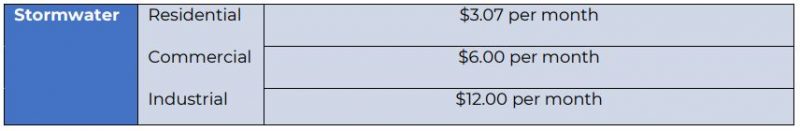

A flat fee means all customers in the same customer class pay the same fee, regardless of how much impervious surface is on individual parcels. The flat fee amount may vary by customer class. Customer class can include those in the example below as well as multi-family, agricultural, institutional, etc.

A uniform fee is also known as a per ERU fee. ERU is an acronym for equivalent residential unit, which is the average impervious surface area on a residential parcel in a community. Customers are charged based on the total impervious surface area on their property.

In the example below, one ERU is 2,500 square feet of impervious surface area. If a parcel has 5,000 square feet of impervious surface, they have 2 ERUs and thus would be charged $6 per month. Like this example, many per ERU fee structures charge 1 ERU for all residential properties.

Now, what is meant by ‘equitable?’ Equitable stormwater management means that the cost to serve a property is equal to the stormwater fee charged to that property.

The cost to provide stormwater services to a property is proportionate to the amount of runoff coming from that property. The best way to estimate runoff is impervious surface area. The more impervious surface area on a property, the greater the cost to service that property. Thus, a fee structure that is based on impervious surface area will be most equitable, at least in theory, but is this the case in practice?

In “The Financial Impact of Different Stormwater Fee Types: A Case Study of Two Municipalities in Virginia,” Amanda Fedorchak calculates multiple fee structures for Roanoke and Blacksburg, Virginia. Each fee structure provides the same total revenue for each city. In the case of Roanoke, residential parcels account for 28.6 percent of impervious surface area. Therefore, a perfectly ‘equitable’ stormwater fee structure would mean that residential customers pay 28.6 percent of revenues. The same logic would hold true for all other customer classes.

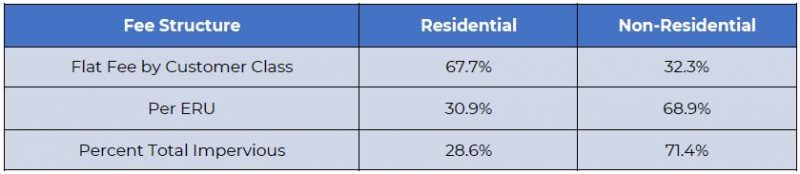

In the flat fee by customer class example, residential customers are responsible for 2.4 times their equitable revenue share. In the per ERU example, residential customers are responsible for 1.1 times their equitable revenue share. The table below shows the results for residential customers and an aggregate of all other customer classes, which is labeled as non-residential. Note that the results are similar in Blacksburg.

The example of Roanoke Virginia shows that charging a flat fee by customer class places a much higher burden on residential customers, charging them more than twice the amount that it costs to serve them. So, it would seem obvious that a per ERU structure would be preferable, yet imperfect, if equity is the goal. However, calculating the exact amount of impervious surface on every parcel is administratively burdensome and can be a cost barrier for establishing utilities in small jurisdictions. As a result, many utilities opt to charge a flat fee for residential customers of one ERU. How does this structure affect equity?

The table below shows that it barely changes the outcome. This result is likely because there is not much variation in the impervious area on a residential parcel while the variation in impervious area across non-residential parcels can be quite substantial.

Therefore, if equitable revenue responsibility across customer class is important to a local government and its stakeholders, moving away from a stormwater fee structure that charges flat fees to all customer classes may be advisable. However, per ERU is not the only option. Tiered fee structures are also a possibility. Contact the EFC for more examples (emkirk@sog.unc.edu).

Sources

[1] Fedorchak, Amanda. JAWRA. 2017. “The Financial Impact of Different Stormwater Fee Types: A Case Study of Two Municipalities in Virginia.”

Need technical assistance? The Environmental Finance Center is here to help!

The Environmental Finance Center at UNC-CH offers free one-on-one technical assistance for small water systems. If you have an interest in our support, contact emkirk@sog.unc.edu.

Visit https://efc.sog.unc.edu/resource/technical-assistance-for-small-systems/ to read more about technical assistance.

5 Responses to “Stormwater Fee Structure Design: Is One Fee Structure More ‘Equitable?’”

Tracy G. Taylor

Thanks for sharing this insightful informantion

Andrew

Insightful post, thanks a lot for sharing this!

Sara

Thanks for sharing the post and thanks for explaining the stormwater fee structure.

Erin

Very well explained post. I’m glad I came here.

Victor Cooperwasser

One method the article failed to mention which, in my opinion, is the most equitable, is to charge each parcel (residential or commercial, i.e., all parcels) based on the impervious area of each parcel (no flat or set of a few tiered fees for residential parcels).

Because the GIS tools are available to do this, measure each parcel’s impervious area and establish an uniform rate for each measured unit simply by dividing the required revenue by the total impervious area of all parcels.

In the end, you may end up with 11 or so “tiers” for residential parcels. Commercial parcels would be billed on the same basis (which is the way most stormwater utilities currently bill commercial parcels.