Post by Austin Thompson, PhD Research Assistant at the UNC EFC

Stormwater management is a growing concern for local governments across the United States. Indeed, as development footprints grow and the climate changes, water quality and quantity issues are mounting, resulting in infrastructural and regulatory costs amidst continually constrained budgets. In general, urban areas have one of two types of stormwater systems subject to EPA permitting via the National Pollution Discharge Elimination System (NPDES): (1) a combined sewer system that conveys stormwater and wastewater to a wastewater treatment plant where it is treated and discharged; or (2) a municipal separate storm sewer system (MS4), which conveys stormwater in a system that is separated from the wastewater system and eventually discharges into a water body. MS4 systems are labeled either small or large, based on the population served.

Stormwater management costs can vary widely across communities and depend on a host of factors. For example, the City of Charleston, SC is increasingly dealing with sunny day flooding, leading to large capital needs to convey stormwater away from the historic downtown and medical district. In contrast, cities like Buffalo, NY do not experience the same sunny day flooding issues, but are subject to combined sewer overflows, a consent decree, and a long-term control plan from US EPA. Smaller municipalities and counties may not be subject to MS4 permitting or have flooding issues, and thus may have minimal stormwater management costs.

Given this variance in associated management scope and costs, there are different approaches to funding stormwater needs. In many cases, local governments may choose to pay for stormwater management through the general fund, using property tax revenues or other general revenue sources to cover budgeted costs. In other cases, local governments may choose to establish a stormwater utility. In these cases, local governments establish an enterprise fund and assess a stormwater fee to cover the costs of the enterprise.

The use of stormwater utilities as a means to manage stormwater varies across the country. Some states require a ballot initiative and a majority vote to establish new taxes or property-assessed fees, making the creation of stormwater utility more politically challenging and a longer process. In California, Proposition 218 requires any new “special tax” to be approved by a two-thirds vote. Further, some areas may have relatively low and consistent stormwater management costs that can be reasonably covered using general revenues. Thus, the administrative burden of creating a stormwater utility and assessing a fee may be moot.

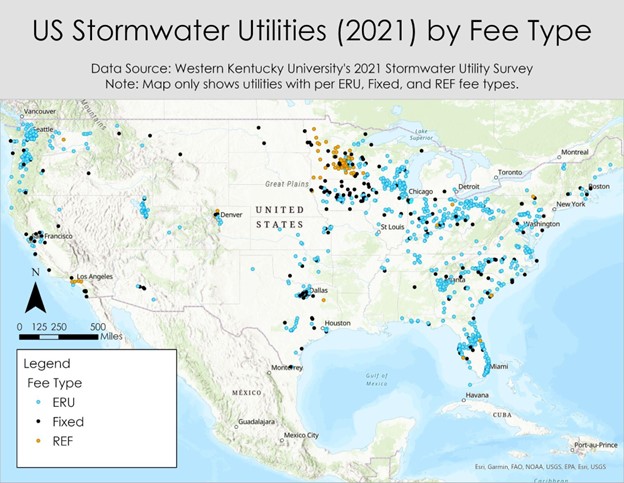

A few entities, including the UNC EFC, have set out to inventory stormwater utilities, their fee structures, and the fee amount. One annual survey from Western Kentucky University (WKU) aims to inventory stormwater utilities across the entire United States. This is no easy feat, as no central data hub exists for stormwater utility information. As of 2021, WKU identified over 1800 stormwater utilities in the US. Using their data, the UNC EFC mapped these utilities using ArcGIS software and an address locator, using a centroid of their city/county and state. This crude analysis was conducted to understand state and regional patterns in the use of utilities and fee structures.

Stormwater Utilities in the US

According to WKU’s survey, all 48 continental states have at least one stormwater utility. Though no utilities were identified in Hawaii and Alaska, according to WEF, a stormwater utility has been established on the island of Oahu, HI (to much debate) and will begin assessing fees in 2023. It also appears as though Anchorage, AK has considered a stormwater utility, but it is unclear if it has been established or is assessing fees. The number of utilities in a given state varies widely, though, from one (CT, NM, NY) to over 200 (MN).

Based on this map, it appears that stormwater utilities cluster around urban hubs in the continental US. This is unsurprising, as urbanization results in both water quality and quantity challenges that require stormwater management and likely benefit from a dedicated source of funding, like a stormwater enterprise fund. Additionally, stormwater utilities appear to be quite popular along the southeastern coast of the US, the Great Lakes region, and the Pacific Northwest, but are far less common in the southwest, the Great Plains regions, or along the Gulf of Mexico.

There are likely many drivers for this clustered approach to stormwater utilities in the US, including climate, land use, local ordinances, state regulations, federal regulations, and general diffusion of ideas and approaches across local governments within geographic regions.

Fee Structures

There are many different types of fee structures recorded in WKU’s survey. When mapping, many different categories across a broad geography can make for a confusing visual with results that are hard to discern. As a result, this analysis focused on visualizing some of the most common fee types, including per equivalent residential unit (ERU), fixed, and residential equivalency factor (REF) fees.

At first glance, it would seem that there are not any discernible patterns in fee structure type across different regions. Nevertheless, a few things stand out that are worth mentioning. First, looking at the map in aggregate, per ERU fee structures are quite popular across the US. Indeed, as LiDAR and other remote sensing data becomes readily available, it is easier (i.e., less costly) to assess fees based on impervious surfaces. Additionally, there are still many utilities assessing a flat fee. This approach has the least administrative burden by far, requiring no measurement or classification for properties. Nevertheless, these structures may result in equity issues and reduce any incentive for property owners to limit the impervious surfaces on their property.

Zooming in on a few regional issues, it appears that utilities along the east coast of Florida are, in large part, opting for per equivalent residence unit (ERU) fee structures. In contrast, utilities in the Minneapolis-St. Paul region opt for residential equivalence factor (REF) fee structures. These approaches are similar, but ever so slightly different. Where ERU structures assess the fee based on a property’s impervious surface area, REF structures consider additional factors such as soil type, land use, and ground slope to assess the fees. The latter approach is highly scientific and likely comes closer to assessing the stormwater runoff generated by a property, but bears a large administrative cost.

Zooming in on a few regional issues, it appears that utilities along the east coast of Florida are, in large part, opting for per equivalent residence unit (ERU) fee structures. In contrast, utilities in the Minneapolis-St. Paul region opt for residential equivalence factor (REF) fee structures. These approaches are similar, but ever so slightly different. Where ERU structures assess the fee based on a property’s impervious surface area, REF structures consider additional factors such as soil type, land use, and ground slope to assess the fees. The latter approach is highly scientific and likely comes closer to assessing the stormwater runoff generated by a property, but bears a large administrative cost.

So, why do these regional patterns exist? Why might utilities in Florida opt for ERU-based fee structures? Why might utilities in the Minneapolis-St. Paul region opt for REF-based structures? Just by looking at the map, it is not totally clear. We do know, however, that local governments are often influenced by their peer communities, including neighbors. Furthermore, state legislation, like Proposition 218 mentioned earlier, influences what a local government can and cannot do, which in turn influences state-level patterns.

Conclusion

A similar, quick analysis could be done along any of the dimensions recorded in WKU’s annual stormwater survey. One item, the fee amount, is likely of interest to utilities as it provides a way to benchmark their fees to neighboring utilities and/or peer local governments. But, as always, UNC EFC recommends proceeding with caution. Many factors influence the cost to manage stormwater and those costs (and the associated fees to cover those costs) should be assessed locally. Additionally, unless a local government has a utility fee, it may be challenging to know each household’s contribution to the cost of stormwater management. As such, these are not “apples to apples” comparisons.

With fee structures, utilities know their constituents. In areas without much commercial or industrial presence and with pretty uniform housing, it may be both easy and fair to assess stormwater fees using a flat fee. If this is not the case, communities should consider how to assess fees to make the costs equitable and affordable for households with ability to pay challenges. Affordability of water, wastewater, and stormwater rates and fees remains an important topic and one that likely will not go away anytime soon. Additionally, constituents increasingly hold their local governments to a very high standard, expecting a variety of high-quality services without raising taxes or fees. As such, local governments will have to continue seeking ways to cut costs, partner, and innovate to meet stormwater needs.

Need technical assistance? The UNC Environmental Finance Center is here to help!

The Environmental Finance Center at UNC-CH offers free one-on-one technical assistance for small water systems. If you have an interest in our support, fill out our interest form here or contact emkirk@sog.unc.edu.

Visit https://efc.sog.unc.edu/technical-assistance/ to read more about technical assistance.

3 Responses to “The Geography of Stormwater Utilities”

Sara

Very insightful post, thanks for sharing!

Katie Gaut

Hello,

I’m working with The Nature Conservancy on a stormwater-related project and would like to, if possible, request a copy of the final spatial point data associated with the 2022 survey. We will, of course, ensure that the data is cited clearly with any and all use. A csv (with lat/long) or shapefile would be ideal. Thank you so much for the amazing work done and don’t hesitate to reach out with any questions!

Thank you,

Katie Gaut

Brian A. Chalfant

Very interesting analysis and post, Austin. You may be interested to take a look at similar work I did using the WKU data (shout out to Warren Campbell!) for my dissertation, which is available @ http://d-scholarship.pitt.edu/35183/; Section 3.5 may be of particular interest to you. I think the role of consultants in the diffusion of stormwater utilities/fees is an intriguing and ripe area for future analysis. Keep up the good work!