By Hope Thomson, Project Director at the UNC Environmental Finance Center

The UNC EFC primarily works with public service providers of environmental services: local governments or other institutions providing water, wastewater, stormwater, or other services to a public population. Working with these utilities, the UNC EFC has an overarching goal of improving its service provision towards financial sustainability while maintaining a high level of compliance with quality restrictions that ensure the public health and well-being of the natural environment. While plenty of work can be done with these entities, only some receive their water or wastewater services from a centralized service provider.

Decentralized users, or people who get their water from a well and/or use a septic system for their wastewater, also need support to protect their health, wallets, and the surrounding environment.

A large body of research has documented how these decentralized users may face additional health burdens from contaminated wells or malfunctioning septic systems. A study by Eaves et al. out of UNC-Chapel Hill’s Gillings School of Global Public Health in 2021 noted that a quarter of wells in North Carolina were above maximum contaminant limits for various heavy metals. Additionally, exclusionary policies throughout history, such as redlining and municipal underbounding, specifically excluded communities of color from the same access to centralized services as their white neighbors. This environmental justice issue is particularly concerning as decentralized users are often unaware of their health exposures or unsupported by government structures in improving their water and sewer access. This can lead to long-term adverse health outcomes that can only be rectified through expensive, time-intensive solutions.

The UNC EFC was interested in learning more about decentralized users and their paths toward improved water and sewer access. Thanks to funding from the North Carolina Collaboratory, the center explored connecting to centralized services and sustainably staying decentralized as pathways towards improved services. An important factor in many decisions along these paths is the cost – to users, utilities, and other stakeholders involved. Understanding these costs and being able to compare them meaningfully provides a tool for decentralized users seeking to improve their services.

Cost to Users – Connecting to Centralized Services

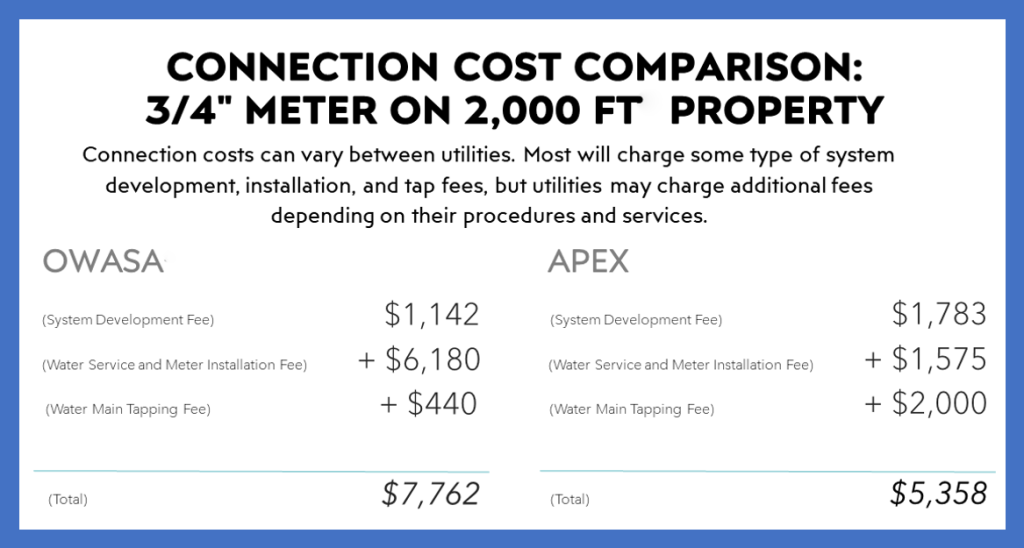

If connecting to a centralized service provider, such as a local government utility, a decentralized user will need to pay upfront to cover the cost of tapping into the system. These fees vary by utility but often cover the “parts and labor” associated with connecting the home. Some of these physical infrastructure improvements may include installing a water meter and pipe extension from the main line to the house. Additionally, connecting the structure’s plumbing to the short-line may be costly.

If connecting to a centralized service provider, such as a local government utility, a decentralized user will need to pay upfront to cover the cost of tapping into the system. These fees vary by utility but often cover the “parts and labor” associated with connecting the home. Some of these physical infrastructure improvements may include installing a water meter and pipe extension from the main line to the house. Additionally, connecting the structure’s plumbing to the short-line may be costly.

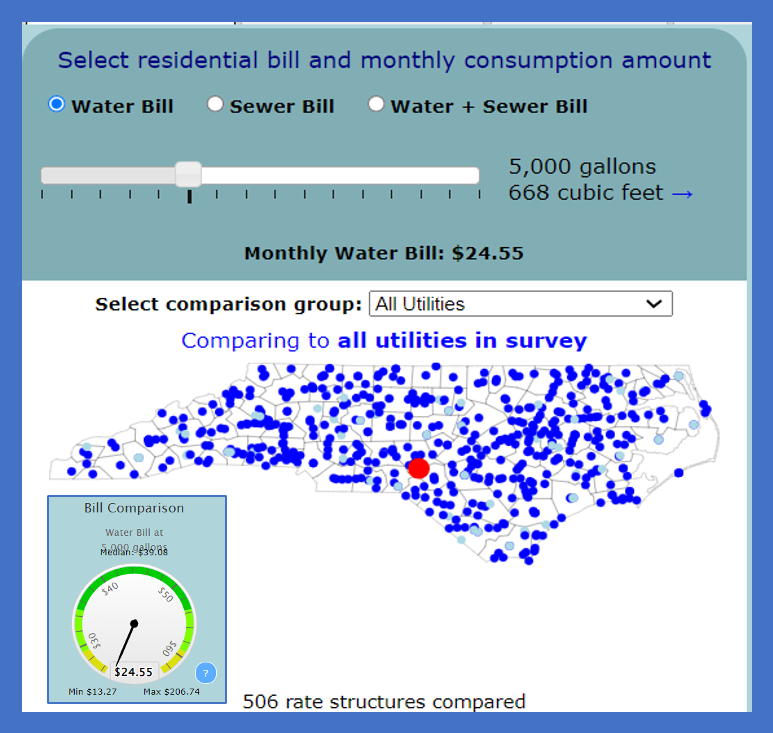

Once a user is connected, they are responsible for paying their monthly water and/or sewer bill. This will vary by utility and by the individual’s usage throughout a month. The UNC EFC prepares a yearly dashboard detailing statewide water and sewer rates for decentralized users curious about their monthly bills. The dashboard is open to the public to use.

There are also resources available from various sources online to estimate household water usage, which can vary greatly depending on the size of a structure and the appliances and individuals it contains.

If a decentralized user chooses to remain decentralized, costs can vary widely. For water access, users often explore point-of-use (POU) filters (water being filtered at an individual faucet, for example) or point-of-entry (POE) filters (water being filtered where it enters the structure). POU filters can range from just $10 to over $1,500, while POE filters can range from $200 to $12,000, depending on the system. Importantly, the type of filter required will depend on what contaminants of concern need to be filtered out. These filters also require maintenance and regular replacement, which carries additional costs.

If a decentralized user chooses to remain decentralized, costs can vary widely. For water access, users often explore point-of-use (POU) filters (water being filtered at an individual faucet, for example) or point-of-entry (POE) filters (water being filtered where it enters the structure). POU filters can range from just $10 to over $1,500, while POE filters can range from $200 to $12,000, depending on the system. Importantly, the type of filter required will depend on what contaminants of concern need to be filtered out. These filters also require maintenance and regular replacement, which carries additional costs.

Cost to Utility

Most local government utilities in North Carolina function as public enterprises, meaning they are expected to bring in enough revenues to cover their current and future costs. And those costs can be large. Water and wastewater are capital-intensive industries, with large sums of money required to build and maintain the system’s infrastructure. Additionally, these utilities are held to tight regulatory standards that protect public and environmental health, so cutting costs while maintaining compliance can pose a challenge. Further, utilities also have to consider future needs and the costs associated with those needs. For example, adding enough new customers may necessitate the expansion of treatment plants. These future costs for capital are sometimes—but not always—accounted for by a “As such, projects that result in additional utility costs, like adding new connections, are carefully considered.

To connect with new users, someone has to pay the combination of substantial connection costs and the preexisting financial pressures utilities face; connection costs are often passed along to the customer. This can change if the new customer is outside municipal limits and will be annexed into the town or city. The effects of annexation on these costs can be complex. To learn more about annexation and its relationship to the extension of services, see the School of Government’s Coates Canon blog post from 2011.

Funding Opportunities

Funding for supporting decentralized users can be sourced from multiple agencies and levels of government – but it may be restricted by the type of applicant or what projects can be covered. A few examples of possible funding and financing streams are included below:

- The Water Well Trust funds low-income homeowners to assist in constructing new wells or septic systems and repairs. Loans are provided up to $15,000 at a fixed 1% interest rate.

- Localized programs provided by a municipality or a county may help cover the cost of decentralized rehabilitation, such as Wake County’s Well and Septic Repair Program, or may target connections to a centralized system, such as the City of Durham’s Septic-to-Sewer Project.

- North Carolina’s State Revolving Funds project eligibilities include options to help decentralized users. On the drinking water side, this could include extending lines or creating a new community water system to address contaminated wells. This could include upgrading, removing, or replacing septic systems on the wastewater side. Importantly, these two funds require a public entity, such as a local government, to be the applicant. Homeowners or decentralized communities hoping to access these funds would need to do so through collaboration with their utility.

UNC EFC’s guidebook including funding streams and other resources focusing on supporting decentralized well and septic users will be published soon. Connect with us on Facebook, X, or LinkedIn to get notified when the guidebook is released!

This project was also introduced in a blog post by the Institute for the Environment in spring 2023.

Summaries of work by the UNC EFC’s collaborators in this work may be available in the coming months. Stay tuned for more information from the Center for Public Engagement with Science and the Environmental Justice Action Research Clinic.