Jeff Hughes is the Director of the Environmental Finance Center.

I’ve come to the opinion that rate structures, particularly those that are designed to promote conservation and water efficiency, may be getting a bad rap or at least getting more than their fair share of the blame for utility budget woes. The stories and complaints tend to go like this – “We changed our rate structure a few years ago and ever since have seen budget shortfalls that have required unplanned for rate increases. Our board is unhappy, our customers are unhappy, the papers are making fun of us and we still don’t have the revenues we need. Damn rates!!”

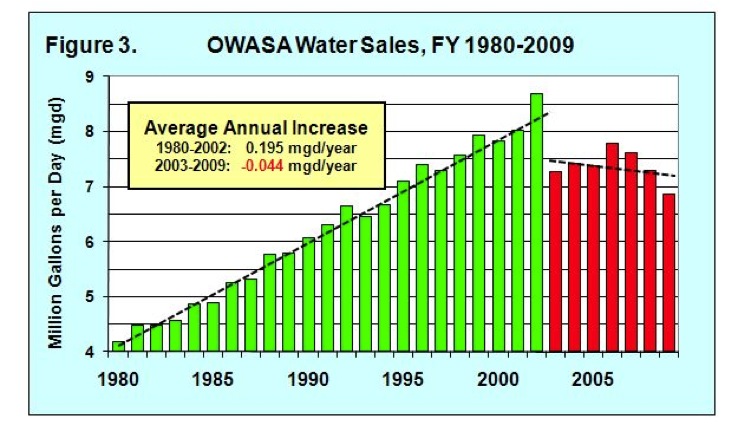

A few years ago when we first started noticing unexpected drops in water demands in the southeast, I was willing to have rate structures share some of the blame or at least take on some of the frustration, but I now believe we have enough data that conscientious proactive utility planners should be able to better predict water sales and design their rates and rate increases accordingly. At the end of the day, its just math, albeit somewhat complicated math given some of the complicated rate structures many utilities have adopted. Revenues are a function of rate structures and water sales. The two are intertwined which makes it interesting. There are also many other factors such as weather and local economic activity that influence revenue generation in a given year. Despite the inherent uncertainty around revenue planning, there seem to be some basic things that can and should be considered at budget time:

Water may be fairly inelastic, but it’s not rigid – use does change with increasing price and any utility that does not take into consideration falling sales when they raise their rates, no longer has much of my sympathy. In the real world, a utility will never be able to predict their actual price elasticity perfectly, but utilities can do what water planners always have done – guess (o.k. – make informed assumptions). If a utility is nervous about revenues, use -0.5 or even -0.7 as the price elasticity (for every 10 percent rate increase, expect a drop of 5 to 7 percent in usage. On the other hand if asking for rate increases scares you more than revenue shortfalls, you could use a lower number like -0.2 but be fully aware by living in a more inelastic world, you have to share responsibility for surprises.

We are “enjoying” one of our era’s big environmental successes – those national standards for water efficiency that were enacted are working – customers are able to serve their needs quite happily with less water. I love my low water-use front-loading washer and I’ll never look back. I’m not as passionate about toilets, but they do their job and use less water as well. This is success — less energy running the pumps to get the water to my house. Cutting out the water that I didn’t need to clean my clothes and flush my toilet. My water utility has some extra capacity to address future service area and economic growth. Who is responsible to take the impact of efficiency into consideration when setting rates? I would argue it’s not the rate structure’s responsibility. It’s basic math, as households use less water, but utilities’ costs don’t go down in the short term, volumetric rate increases need to go up faster than revenue requirements particularly if a utility has relatively low base charges. If a utility projects needing 10% more revenue each year for the next 5 years, it’s entirely possibly that taking into consideration basic math, elasticity and falling demands, the volumetric rate may have to be increased 12 to 15% a year. It’s not a happy fact, but it’s not the rate structure’s fault – blame all those engineers that decided to design water efficient appliances for a living.

Weather will rain on your parade or not. In the southeast, we’ve had quite a roller coaster ride over the last 10 years – hundred year droughts bumping up against 50 inch rain years. This comes at a time, when many suburban water utilities have adopted increasing rate structures to send stronger pricing signals (see item 1) to customers for water irrigation. It may rain or may not in a given year. A utility may have to restrict irrigation or it may not. The challenge is that increasing block rate structures lead to feast or famine years. A back of the envelope calculation can show that potential weather swings can lead to 5 to 10% revenue swings for many utilities. These revenue swings can and should be at least modeled and not a complete surprise.

Source: Orange Water and Sewer Authority

Taking into account all the above considerations does make for conservative financial planning and may lead to “boon” years in which revenues exceed protected and budgeted revenue needs. Utilities, like Charlotte-Mecklenburg Utilities or The Water Works Board of Birmingham, that have adopted financial plans that have set ambitious targets for reserve funds, rate stabilization funds, and pay as you go to debt ratios can usually put these funds to use in a way that benefits water customers (lower capital costs, accelerated capital project implementation). Creative utilities that want to mirror private companies that have good utilities could always consider paying dividends – more on this option in a future post.

I’ve never met a rate structure I completely love, and there are many with huge character faults but even the most finicky rate structure usually has a redeeming characteristic that met a particular objective that led to it’s adoption. We think there are better rate structures out there that may be better suited to decreasing and variable demand environment and we are hard at work testing alternatives. In the meantime, while it is difficult and requires unpopular decisions, revenue stability and sufficiency is possible with every rate structure as long as the projections take into consideration what’s happening around us.

//

2 Responses to “Rate Structures Don’t Kill Budgets, Inaccurate Projections Do”

Paul Lauenstein

Mr. Hughes,

I read your article about water rate structures with great interest. Here in Sharon, MA we have a steeply ascending block rate structure. Sharon has reduced its water usage by approximately 100 million gallons per year (20%) since the 1990’s despite an increase in population. More efficient water usage is saving the town money, improving its water quality, and protecting local ecosystems.

Lately, some water committee members have proposed to scrap our conservation-oriented water rates and replace them with a high fixed fee and a single usage rate, which would strip away most of the incentive to conserve.

At the end of your article, you mentioned that you are investigating alternative rate structures. I would be interested to discuss this with you at your convenience. My phone number is 781-784-2986. My email address is lauenstein@comcast.net.

Paul Lauenstein

Jeff Hughes

Paul,

Thanks for your comments. Someone from the EFC will follow up with you shortly to discuss our work with alternative rate structures. I don’t think switching to a higher fixed fee and lower variable rate will necessarily increase total revenue — it will mainly reduce revenue swings from year to year. A finance policy that creates and maintains a rate, or more accurately, a “revenue stability” fund is another alternative to weathering revenue swings without reducing price signals.

Jeff